Stubby: A Canine Hero of World War I

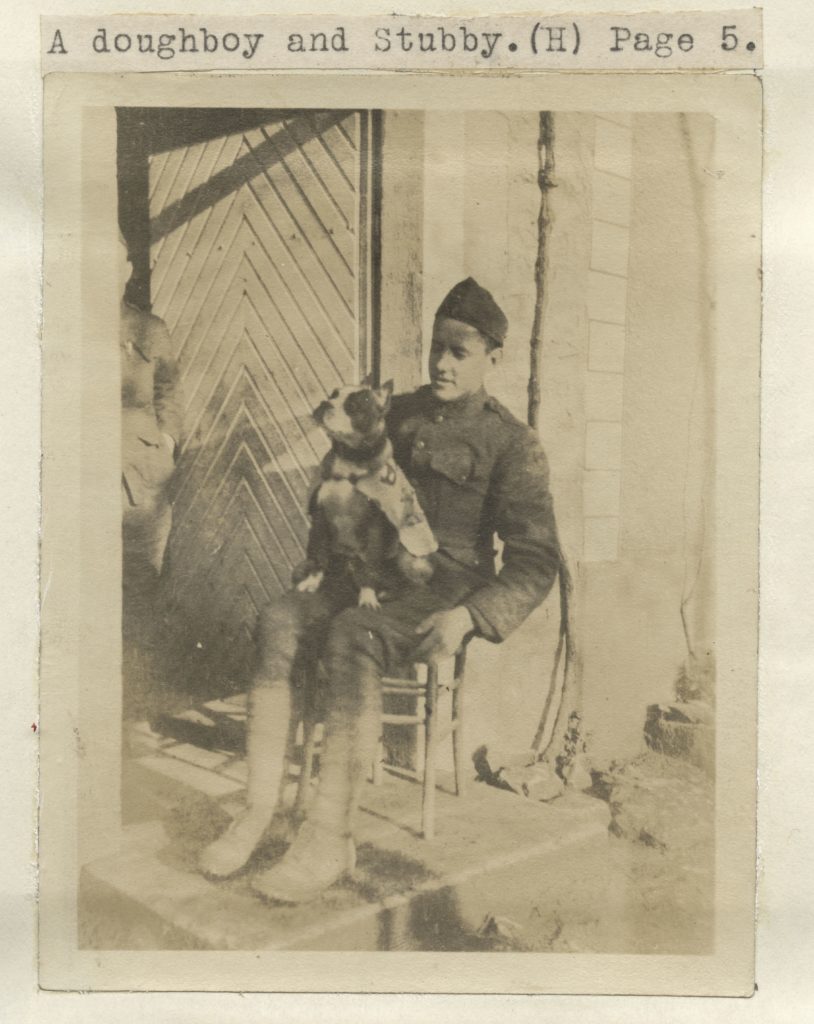

Robert Conroy and Stubby. Connecticut State Library

By Bobby Shipman

When we think of the U.S. Army we think of green and camouflage uniforms. We think of tanks and Jeeps. We imagine a general yelling orders at his soldiers. We don’t usually think of dogs. That doesn’t mean dogs can’t be in the army.

One of the most famous U.S. Army dogs was named Stubby. Long before that, he roamed the streets of New Haven. He was a stray dog. But one summer day in 1917 he was adopted by a soldier. Stubby became a soldier, too. He served on the battlefields of Europe. He fought, in his own way, alongside the soldiers. He even captured a prisoner! The story of Stubby is one of courage, friendship, and a true American hero.

How It All Began

It was a warm summer day in 1917. World War I had been raging in Europe for three years. Our allies needed our help.

The Connecticut National Guard’s 102nd Regiment was training. Their camp was on the grounds of Yale University in New Haven. A stray dog wandered by. He was a small, brown and white bulldog. As the soldiers marched, the dog marched along. He followed them to lunch. He ate what they ate. Robert Conroy took a liking to the persistent pup. He adopted him. He named him Stubby, after his short stub of a tail.

Stubby was Conroy’s best companion in training. He learned to drill just like Conroy. He could even salute! Soon it was time for Conroy and the other soldiers to leave for France. Conroy couldn’t leave his companion behind!

It was against the rules, but Conroy snuck Stubby to France. His commanding officer was angry at first. He wanted to send Stubby home. But then Stubby saluted. The officer decided to let Stubby stay.

Stubby Earns His Stripes

Stubby and the 102ndRegiment reached the battlefield in France in February 1918. It was difficult for everyone. The sound of bombs and gunfire was loud. Stubby was not afraid. He ran across the battlefield. He found wounded soldiers and barked until help came. He learned to tell an American from an enemy soldier.

The soldiers fought in trenches dug into the earth. Stubby soon learned his way around the maze of trenches. He helped out by killing rats. He learned to smell poisonous gas and alert the soldiers of a gas attack. The soldiers made him a dog-sized gas mask so he would be safe.

But Stubby’s most famous accomplishment was yet to come. In one battle he spotted a German soldier. He jumped up and bit the soldier. On the butt. Hard. He refused to let go until Americans came and took the German prisoner. Stubby had captured a prisoner of war!

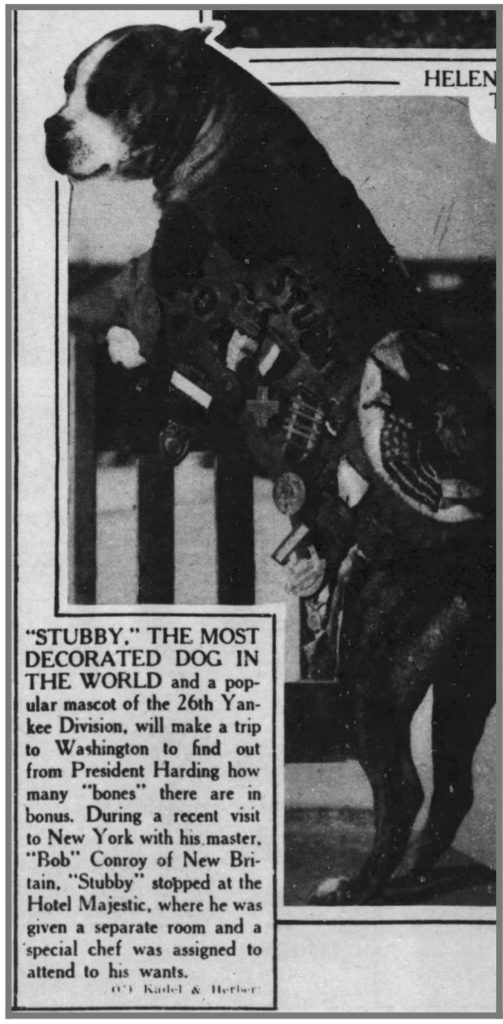

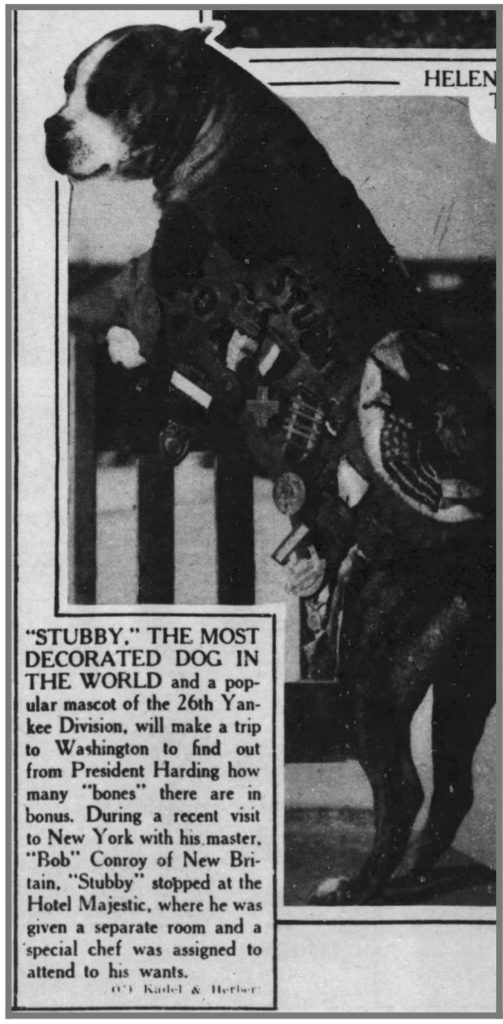

The war ended on November 11, 1918. Many lives were lost. Much of Europe was destroyed. Stubby had fought in 17 battles in just 9 months. He had been injured and survived. Grateful French women made him a jacket. It was covered in medals.

Stubby in a parade wearing his coat and medals. Library of Congress

Parades for Stubby

When Conroy and Stubby came back to America, Stubby was celebrated as a hero. Stubby wore his jacket proudly as he marched in parades. He met three presidents.

Conroy decided to go to Georgetown University in Washington, DC, to study to be a lawyer. Stubby went with him. He became the university mascot. Stubby had come a long way from the streets of New Haven.

Stubby died in 1926. Instead of being buried, his body was preserved. It is on display in the Smithsonian Museum of American History in Washington, DC. The New York Times, the most famous newspaper in America, printed his obituary.

Hartford Courant, March 18, 1926

But even 90 years later, Stubby is remembered. In April 2018 a movie about him, Sgt. Stubby: An American Hero, came out. There is a new statue of him in Middletown, and a plaque in his honor in the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri. These are fitting tributes to the unbreakable courage of an unlikely hero.

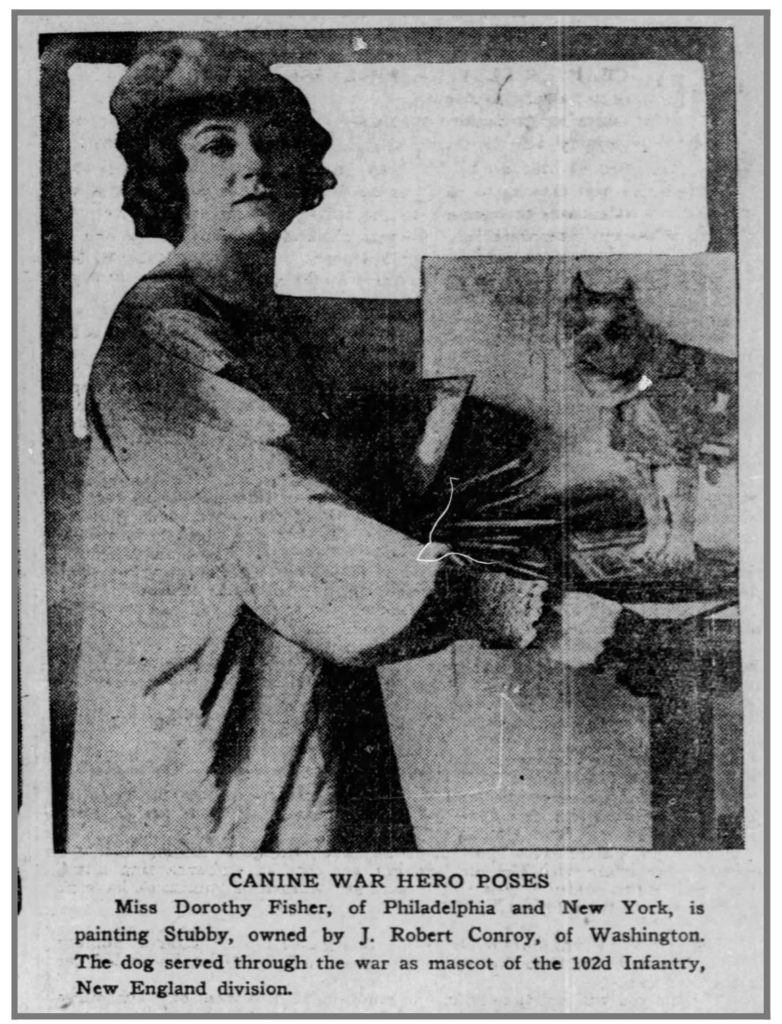

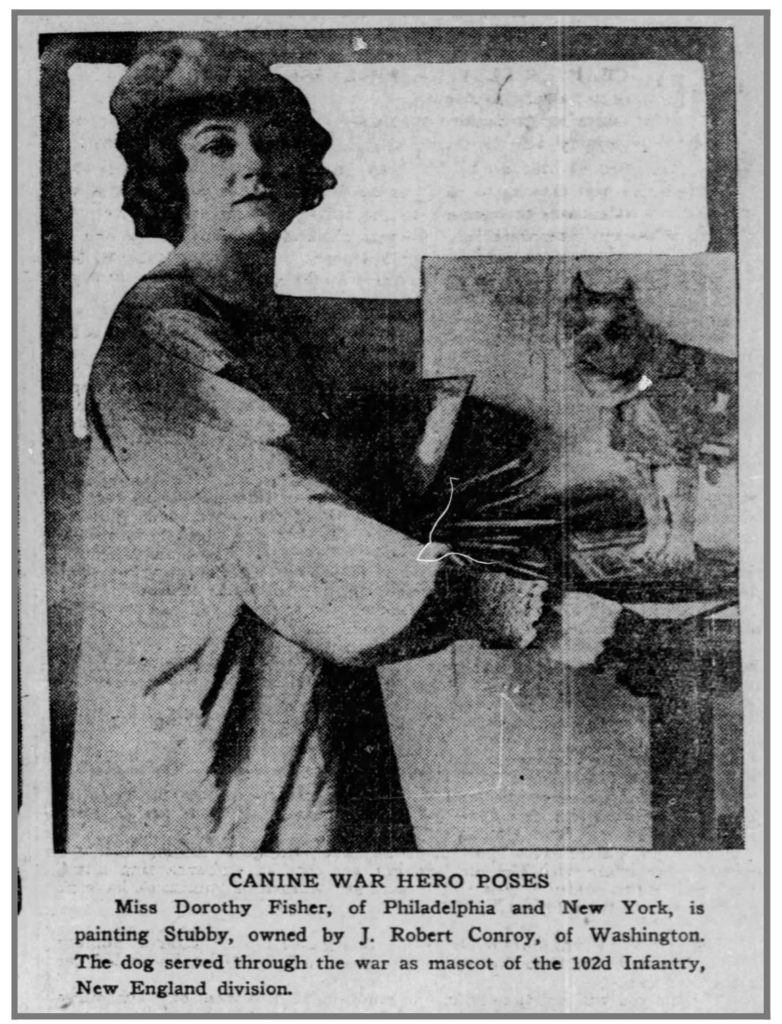

Philadelphia Inquirer, May 15, 1923

Hartford Courant, January 21, 1923