Daily Life in a Colonial Town

Printable PDF

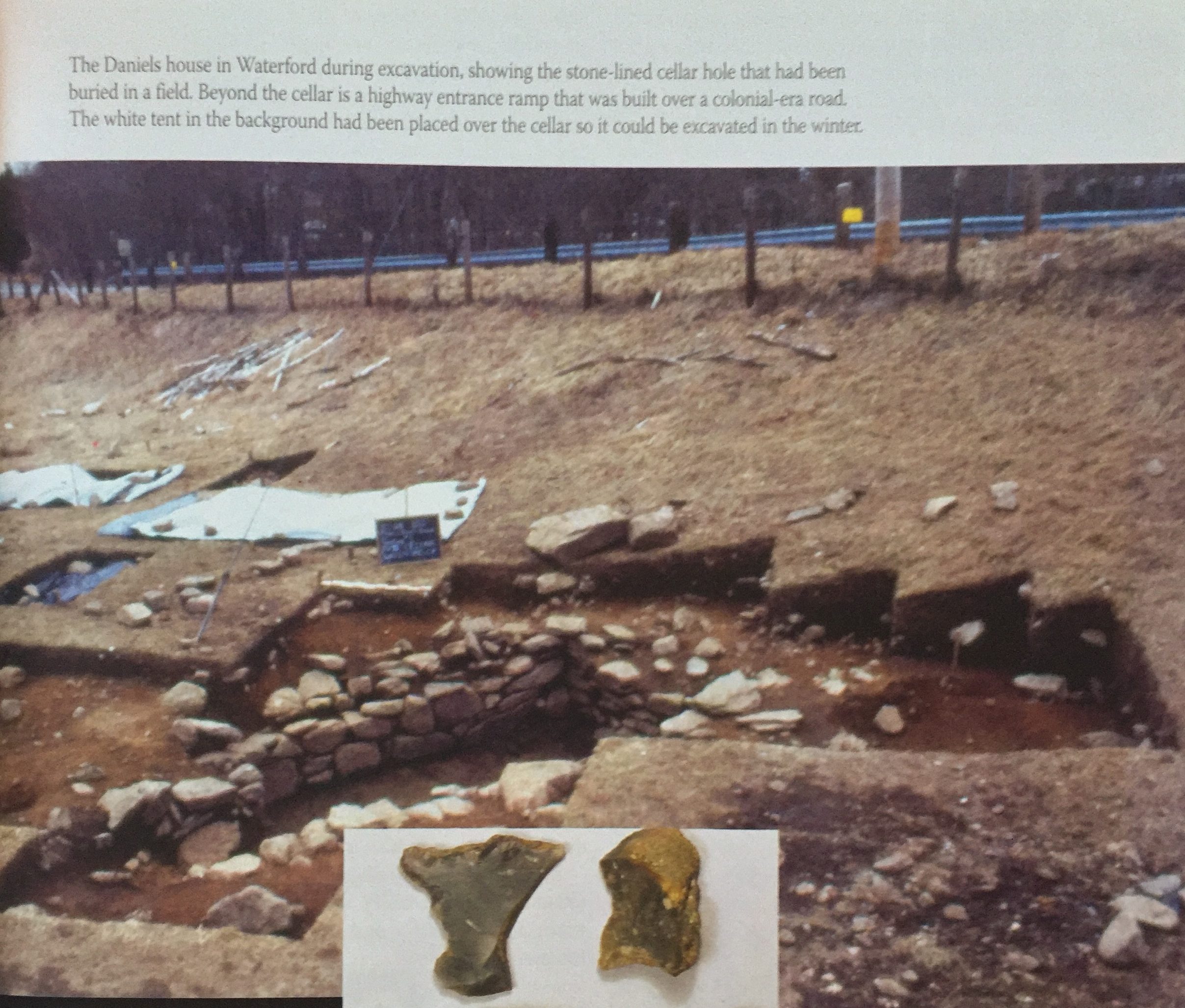

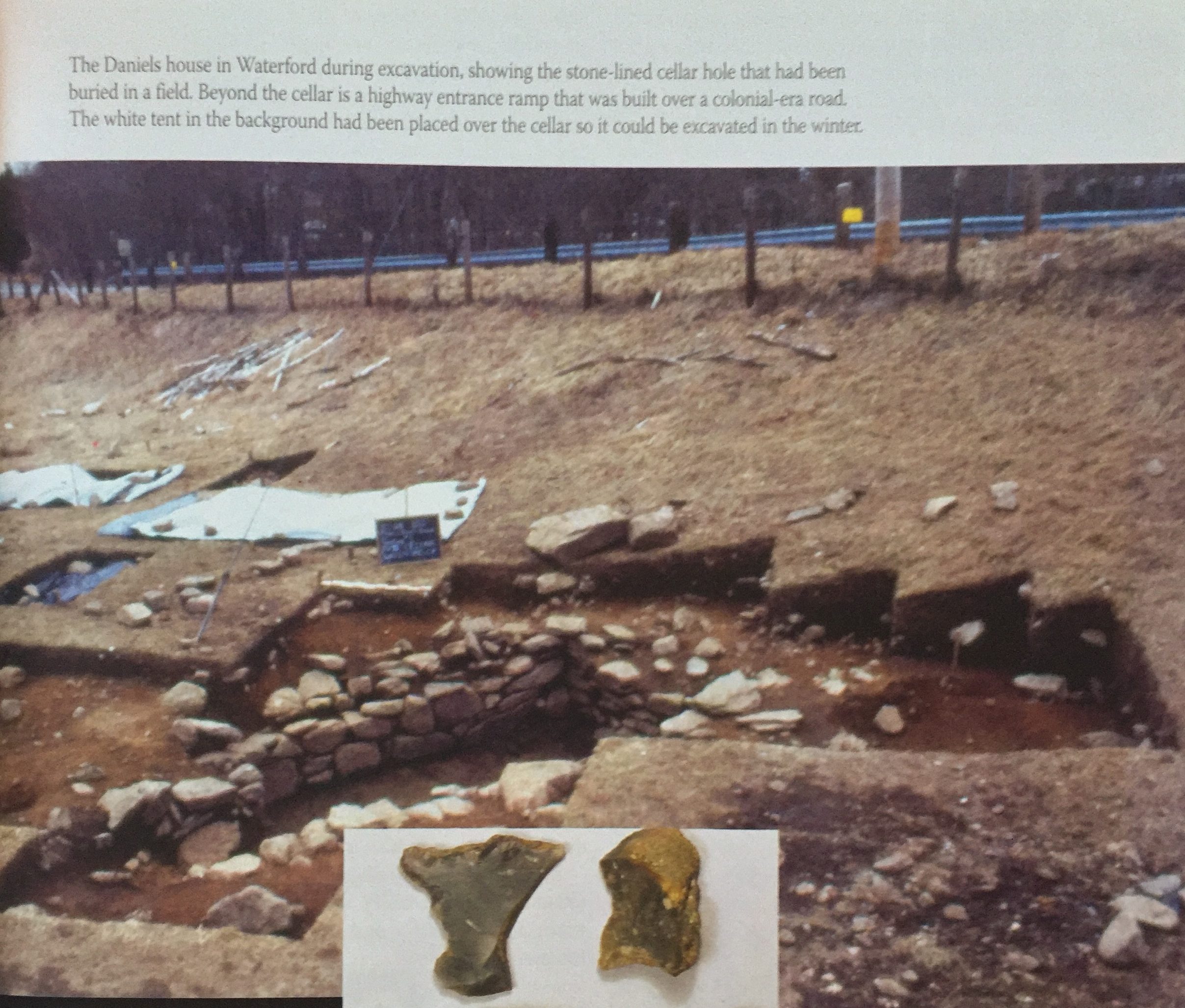

Cellar hole of the Daniels House, Waterford. Highway ramp in the background, built over a colonial-era road. From “Waste Not, Want Not,” Connecticut Explored, Fall 2012. photos: Archaeological and Historical Services Inc.

What do you do with things you don’t need anymore? Do you put them in the recycling bin? Do you put them in the trash?

Imagine living in early Connecticut. The garbage truck did not come to pick up your trash every week. Colonial boys and girls threw their trash out in the yard!

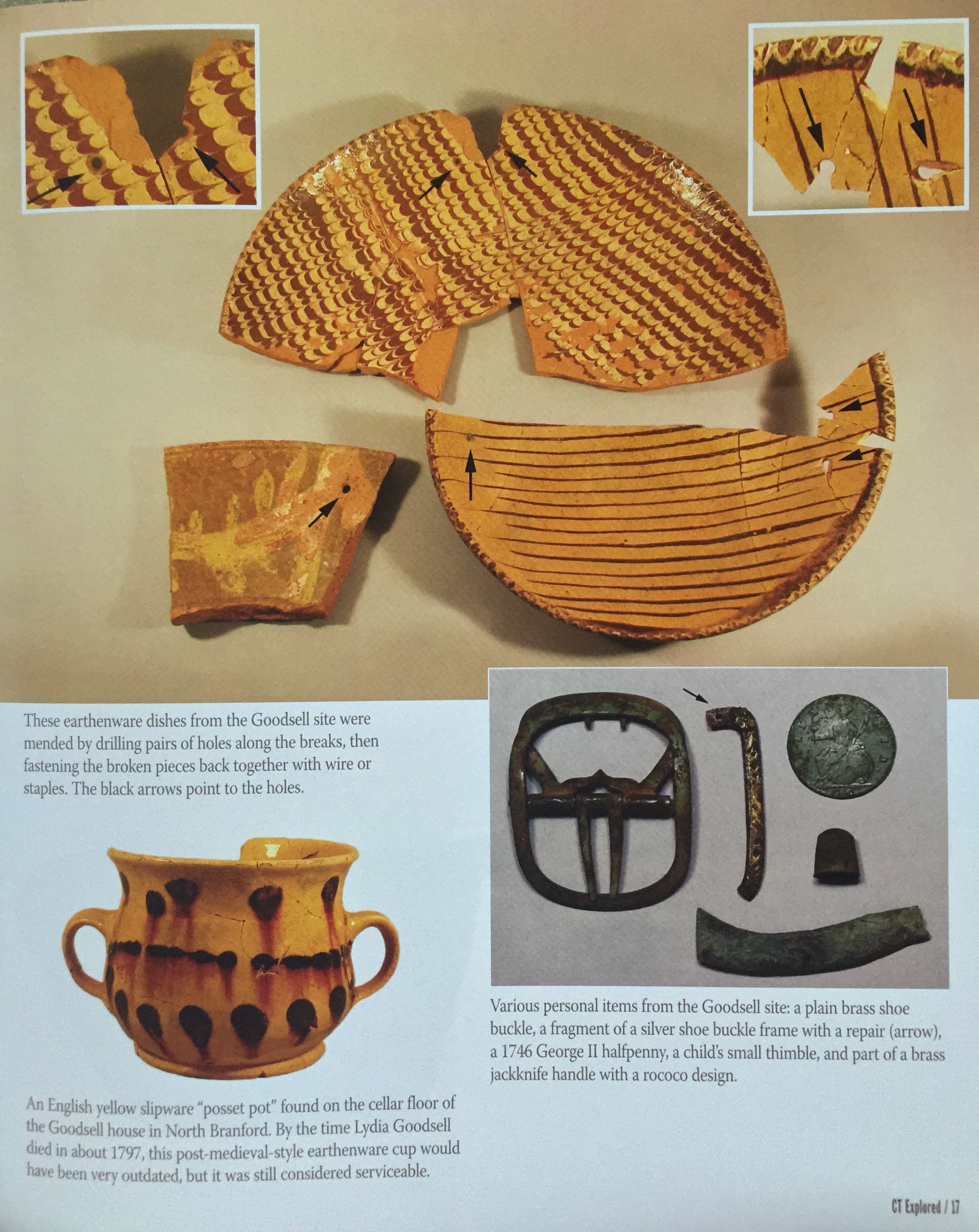

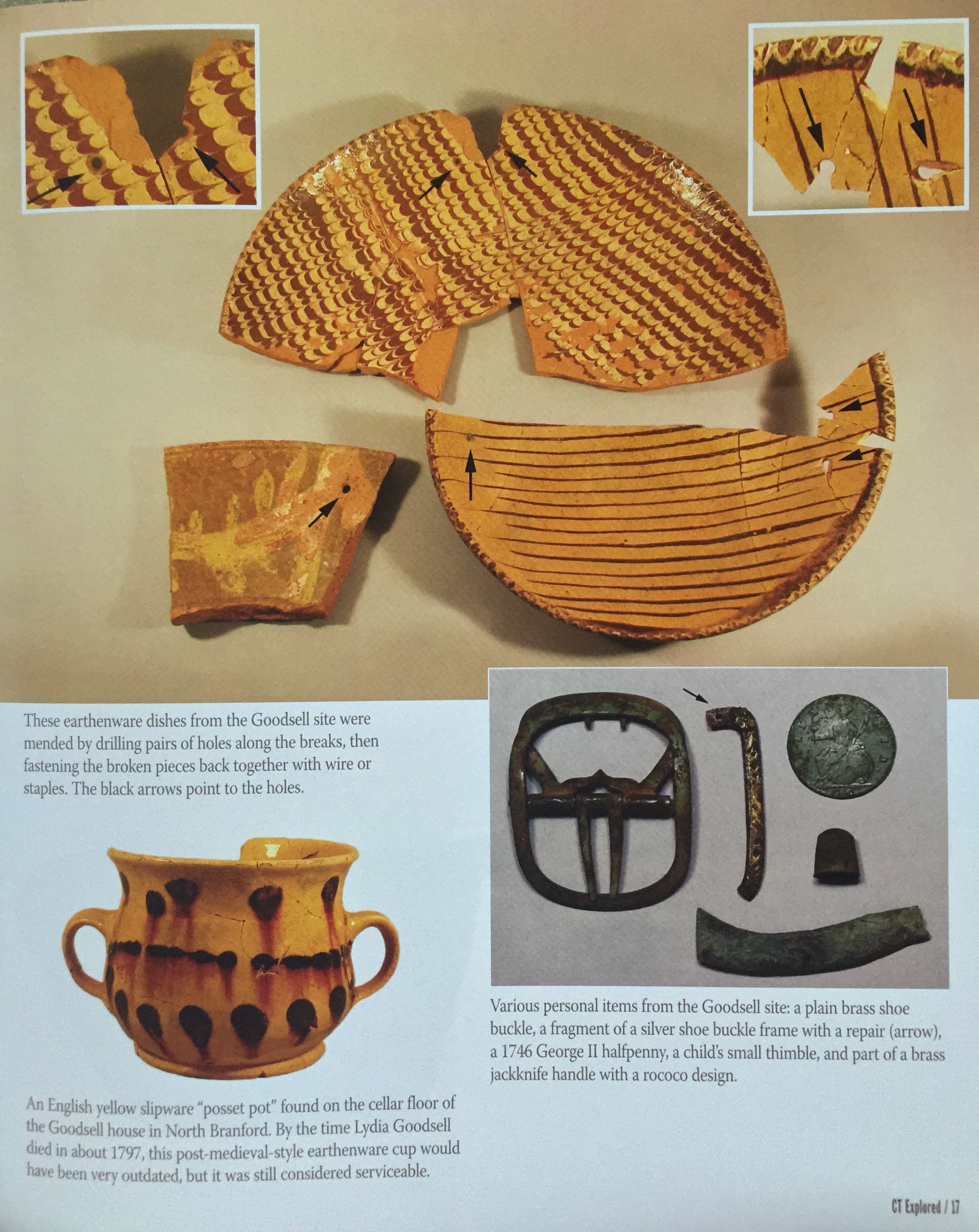

top and lower left: Earthenware dishes. inset, right: Brass shoe buckle, part of a silver shoe buckle, halfpenny, small thimble, and jackknife handle. All from the Goodwill site. From “Waste Not, Want Not,” Connecticut Explored, Fall 2012. photos: Archaeological and Historical Services Inc.

But first they would try to fix the item or turn it into something else. Lydia Child, author of The Frugal Housewife (published in 1829), said: “Nothing should be thrown away so long as it is possible to make any use of it.”

After it was used up, it was thrown in the garbage pile in the yard. Newer things went on top of older things. The pile eventually got covered up with dirt and leaves.

These colonial garbage piles are called middens. We can tell a lot about the life in a colonial town from these colonial garbage piles.

Archaeologists look for clues in the earth to learn about the past. They dig up middens. They also dig where a farmhouse once stood.

Hollister site. Photo: Walter Woodward

Archaeologists know which animals settlers hunted for food. They know they made things from the bones and fur. Archaeologists have found black bear, fox, skunk, raccoon, beaver, and muskrat bones where a farmhouse once stood.

Families would take extra food to the market to trade. They traded for things they needed but could not make, like glass or metal tools. In these cellar holes, archaeologists find tools, dishes, and toys.

So Much Work to Do

Being a Connecticut colonist was not easy! There were many jobs to do. A man might be a minister, lawyer, carpenter or shoemaker, but he was also a farmer. Early Connecticans had to grow or make almost everything. They grew corn, peas, squash, and tobacco. They raised sheep, cows, pigs, and horses.

Men weren’t the only ones in the family who worked. Lydia Child also said, “Every [family] member should be employed either in earning or saving money.”

Men and boys worked outside most of the time. They plowed the fields and planted the crops. They took care of the crops while they grew, and then picked the crops at harvest time. They also had to make time for their other job—such as making shoes if they were shoemakers.

Sewing items found at the Sprague house site. From “Waste Not, Want Not,” Connecticut Explored, Fall 2012. photos: Archaeological and Historical Services Inc.

Women and girls had many jobs too. They worked mostly in the home and kitchen garden. They cooked and preserved food to eat during the winter months.

Women churned butter from milk from their cows. Fruits from their orchard and vegetables from their garden were dried or sealed into jars. Meat was dried and salted to preserve it.

Women also took care of the sick by giving them herbs and other home medicines. Women spun yarn from sheep’s wool, wove cloth, and sewed clothing. They made quilts for their beds.

There was so much work that some families owned slaves to do the work. Enslaved people were not paid for their work and had no freedom. They were controlled with laws and violence. For more than 200 years, it was legal in Connecticut to hold people as slaves. Slavery was abolished in 1848.

All Work and No Play?

Working on the farm wasn’t all that colonial families did. Children also went to school when they weren’t needed on the farm. Their fathers served in the local militia and might hold a town office.

The Congregational Church was a very important part of colonial town life. Families usually sat by the fireplace after supper and read the Bible together. Sunday was the one day of the week that no one worked. The “Sabbath” or “Lord’s Day” began at sunset on Saturday and lasted until sunset on Sunday. The church service lasted for hours. The minister gave a long sermon, or speech. The Congregational Church did not celebrate Christmas or Easter.

What Would Your Garbage Tell Archaeologists?

Many things have changed since colonial times. We no longer throw our garbage out our back door! If you did, what would it tell future archaeologists about what you ate and what you did today?

This article is based on:

“Waste Not, Want Not: What a Colonial Midden Can Tell us,” by Ross K. Harper, Connecticut Explored, Fall 2012

The Connecticut Colony by Kevin Cunningham, Scholastic, “A True Book” series, 2012

The Connecticut Colony by Dennis Brindell Fradin, Children’s Press Inc., 1990

Learn More:

Listen to this podcast about a 2016 archaeological dig of a colonial home site in Wethersfield:

Grating the Nutmeg: “Connecticut’s Most Important Archaeological Find Yet”

Glossary

Archaeologist a person who studies history through digging in the ground to find things that p can tell him or her about what happened there in the past.

Frugal costing as little as possible

Harvest the season when crops are gathered

Preserve to prepare to be kept for future use

Sermon a speech that is about religious instruction