Benedict Arnold: A Traitor Among us

November 16, 2017Nurse Pioneer Martha Minerva Franklin

November 18, 2017

Walter J. “Doc” Hurley

“Be of service, get an education, and don’t quit.”

Walter J. Hurley

Walter J. Hurley was born on March 2, 1922 in Albany, Georgia. His family moved to Hartford, Connecticut when he was a year and a half old. His father wanted his son to become a doctor. He began to call him “Doc.” The nickname stuck.

Doc’s father died when he was six years old. Money was scarce. Doc sometimes went to a meat processing plant and asked for scraps of meat. Kids made fun of him but he needed to help his family.

Doc loved playing sports. He really liked football. He played with the neighborhood kids in empty lots. No one had uniforms. They used rags for padding. Sometimes the city’s Parks and Recreation workers supervised a game. They saw that Doc had talent.

Adults reminded Doc that education was important. He tried to do his best in school. He liked to memorize poetry. As an adult he could recite poems he learned as a boy.

When Doc was 14 years old, Jessie Owens won four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics. There were very few role models for black athletes then. Doc was inspired that a black man could reach such stature as an athlete and represent the United States.

At Weaver High School Doc earned letters in four sports in one year. He got a letter in football, basketball, track, and baseball. Track and baseball were played during the same season. Doc would wear his baseball uniform to track meets. After his track meet he would go play in the baseball game. After the game, he would go back to the track meet to see how he’d done.

One day in his senior year, Doc was called to the principal’s office. He thought that he was in trouble. Instead, he was introduced to a recruiting scout from Virginia State University. The scout offered Doc an athletic scholarship to attend the university. The scholarship meant he could go for free.

University and Marines

Doc got on a bus to go to Virginia State. He experienced segregation for the first time when the bus arrived in Washington DC. The black passengers had to move to the seats at the back of the bus.

Doc excelled in athletics at Virginia State. He made friends. He met Gwendolyn Bannister who he later married.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. America was at war. It was World War II.

Doc decided to leave college and fight for his country. He signed up to be a Marine. The American military was segregated. He was sent to Montfort Point where black marines were trained. His officers and drill sergeants were white. Doc saw that this was wrong. He served his country fighting in Saipan and China.

After the war Doc married Gwendolyn. He earned his college degree. He got a job as a high school coach in Virginia. His teams won state championships in three sports. He also worked as an athletic official.

During the summers he and his family returned to Hartford. He worked for the city’s Parks and Recreation Department. He earned a Master’s Degree from Springfield College.

Return to Hartford

In 1959 Doc and his family moved back to Hartford to help take care of his mother. He looked for a job teaching and coaching. His wife Gwendolyn got a job teaching fifth grade.

His old neighborhood had changed. His family used to be one of the few black families there. Now many black families lived in the city’s North End. But he was surprised that all the city’s high school coaches were white. He was told that the Hartford schools were “not ready for a black coach.” He found other jobs and hoped he’d be able to coach in the future.

Doc worked for the city’s Parks and Recreation department. He officiated at sporting events. He also worked with the Trinity College National Youth Sports Program.

Doc saw and met many black athletes when they played in Hartford in the Negro Baseball League. He saw Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and Jackie Robinson play.

Doc finally got a teaching job. He taught physical education and was a coach at Barnard Brown School in Hartford. He also taught at West Middle School and Northwest Jones Middle School. But he wanted to be a high school coach.

The evening of April 4, 1968 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. The black community in Hartford, like black communities across the country, was shocked and horrified. Many people gathered in the streets to express their feelings. Some were so upset that they began destroying property. School leaders worried that students might cause trouble at school the next day. Doc was asked to go to Weaver High School to talk to students. He was respected in the community. He was able to comfort the students and hear their anger and pain.

Doc was hired as assistant principal at Weaver High School. When he was finally offered a coaching job he said no. He felt the job should go to a younger person. He recommended Turk Cuyler. Cuyler became the first black coach in the Hartford school system.

Doc retired in 1984 as vice principal of Weaver High School. Every summer until 1996 he was the director of the National Sports Program at Trinity College.

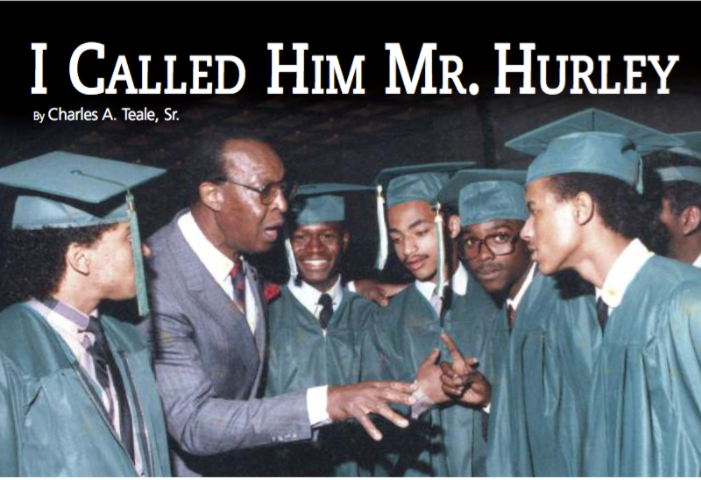

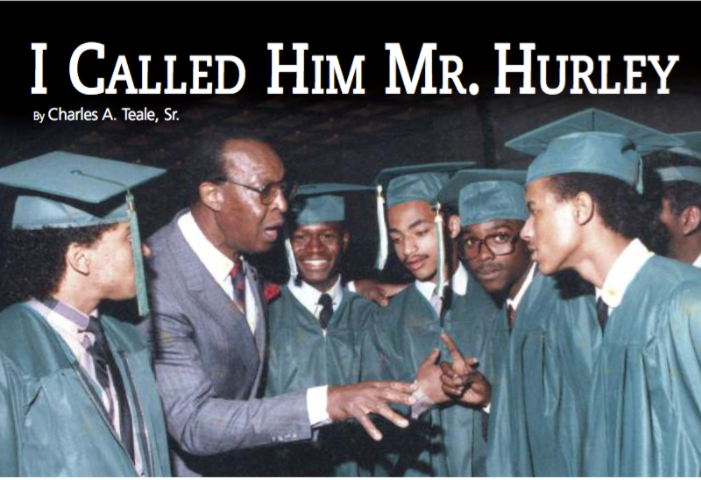

Doc Hurley had a positive influence on many kids in Hartford. Hartford Fire Chief Charles Teale, Sr. was one. Here’s Chief Teale’s story in his own words.

Connecticut Explored

“I Called Him Mr. Hurley”

by Charles Teale, Sr.

I dropped out of school at age 14. That I achieved what I have, I owe mainly to one man. I called him Mr. Hurley.

I was 17 when it finally dawned on me. I had made a huge mistake by dropping out of school. For a couple of years, I was able to find work. I got a job washing dishes or bussing tables. With the money I earned I could hang out with friends. I had enough laughs to make me forget all about school.

Then the day came when I could not find a job. All of the good times ended. I realized that I was about to turn 18 and I had nothing going for me.

That year, 1973, Pratt and Whitney Aircraft was hiring. They were paying big money. However, Pratt and Whitney didn’t hire everyone. They hired people who had an excellent work history and references. I had neither.

So I paid a visit to the only man I knew could help me get hired. Everyone knew who he was. When I was in the fifth grade he was my gym teacher. By the time I was 17 he was assistant principal at Weaver High School.

His name was Walter J. “Doc” Hurley. Everyone else seemed to call him “Doc”—a nickname given him by his father. But I called him Mr. Hurley.

It took a few trips to get up the nerve. I finally drove up to his house at 289 Ridgefield Street in Hartford. I knocked on his door. When he answered, I said, “My name is Charles Teale. I used to be one of your students and I think I’m in trouble. I need your help.”

He said, “Come on inside. Have a seat. What seems to be the problem?”

I told him I had dropped out of high school. For a while he simply paced the floor, shaking his head from side to side.

Then he said, “I can’t believe you gave up on your education. What do you expect me to do?”

I told him that I hoped he would give me a reference. He said, “I’m not going to help you to get a job, because you’re going back to school!”

I said, “I can’t go back to Weaver, I’ll be an 18-year-old freshman.” He replied, “You can get a GED. With that you can go on to college.”

In an instant the feeling of despair lifted. I came to realize that it was not all over for me. Before I left he told me three things: “Be of service, get an education, and don’t quit.”

The paper I wrote his words down on stayed with me for 10 years. Time and time again my persistence was tested. Finally I succeeded. I accomplished all of my academic and professional goals.

I was determined to repay the community. I decided to teach and tutor adult education students.

Mr. Hurley told me how he founded the “Doc” Hurley Scholarship Fund. He invited the basketball teams from Virginia State (his alma mater) and Hampton University to play a demonstration game in Hartford. For the next 37 years, an annual basketball tournament raised money for the scholarship fund. He estimated the fund provided scholarships to more than 500 students.

Toward the end of his life, I went to visit him. I said, “Let me write your autobiography.” It took 43 interviews at home, in the hospital, and a nursing home in Bloomfield. The book eventually topped 200 pages. When I had written just 104 pages, he looked at it and exclaimed, “Chief, you deserve a pat on the back!”

Sadly, on February 9, 2014, Walter J. “Doc” Hurley died. At his funeral I vowed to finish his book. On February 18, 2015 we launched his book at the place where it all began, the Hartford Public Library. It was the most moving experience I had ever had.

Today, the “Doc” Hurley Scholarship Fund continues under the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving. Foundation president Linda Kelly said, “Mr. Hurley’s commitment to improving the educational opportunities for the young people of the Greater Hartford community is unparalleled and steadfast. We are proud to continue his legacy through this scholarship fund.”

Charles A. Teale, Sr. is the retired fire chief of Hartford, Connecticut. This story is slightly revised from his story “I Called Him Mr. Hurley,” Connecticut Explored, Fall 2015.

The biography of Doc Hurley is adapted from an essay by John Karrer for the West Hartford Public Schools.

Sources:

“The Making of a Legend: The Life and Times of Walter J. “Doc” Hurley,” Sr. by Chief Charles A. Teale, Sr., Ret.

Newspaper articles in The Hartford Courant, Weaver High School yearbooks, memorabilia and personal interaction with Mr. Hurley by John Karrer