The State Animal: The Sperm Whale

Mother and baby sperm whale. Gabriel Barathieu, httpwww.flickr.com/photos/barathieu/7277953560/

Sperm whales live in oceans all over the earth. They like deep water. They will dive over a mile hunting for squid to eat.

At its deepest point, Long Island Sound is 320 feet deep. Whales rarely enter the sound’s shallow waters. So why is the sperm whale our state animal?

The Connecticut General Assembly designated the sperm whale the state animal in 1975. The state’s website says that they chose the whale for two reasons. The first was because of its connection to our state history. The second was because it is an endangered species.

Connecticut’s Whaling History

Charles W. Morgan, 1924. Library of Congress

During the 1800s, the whaling industry was an important industry in Connecticut. Many ships sailed from Connecticut ports in search of whales. New London and Mystic were two of those ports.

Whales were valued for their oil. Whale oil was used in lamps. It burns clear and bright and without smoke or odor. Whale oil was used to help machines’ metal parts glide smoothly against each other. Whale oil was especially important during the industrial revolution.

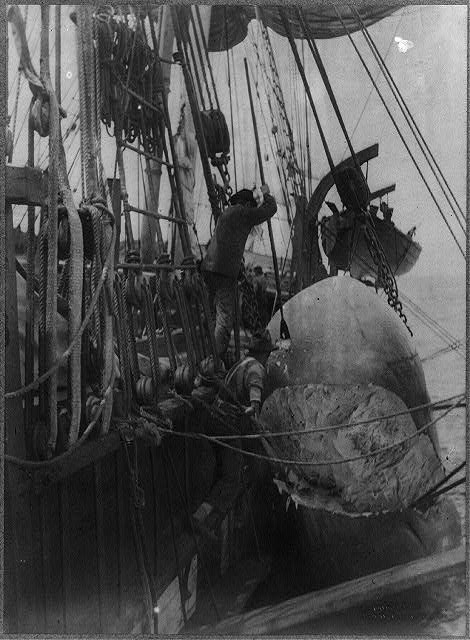

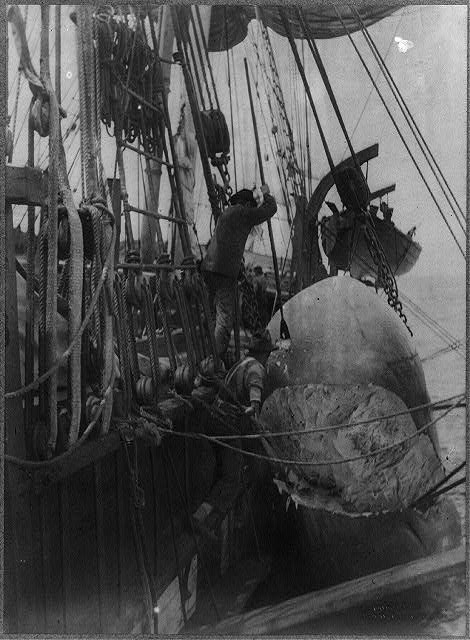

The sperm whale was prized for its oil. The oil was collected in two ways. It was collected from reservoirs in the animal’s head. Another way was to heat large chunks of blubber in huge pots on the ship’s deck. The oil melted from the blubber. The oil was collected in barrels and stored inside the ship.

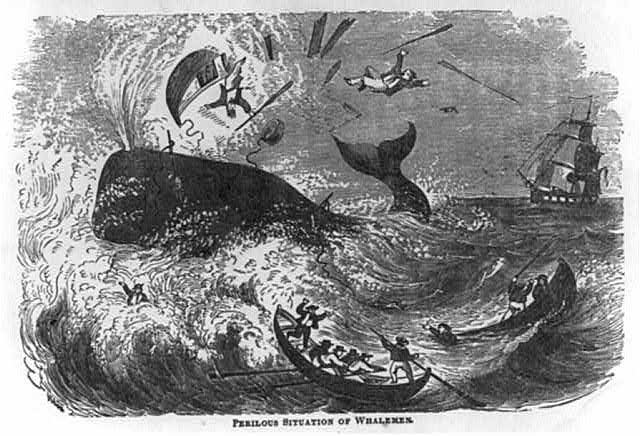

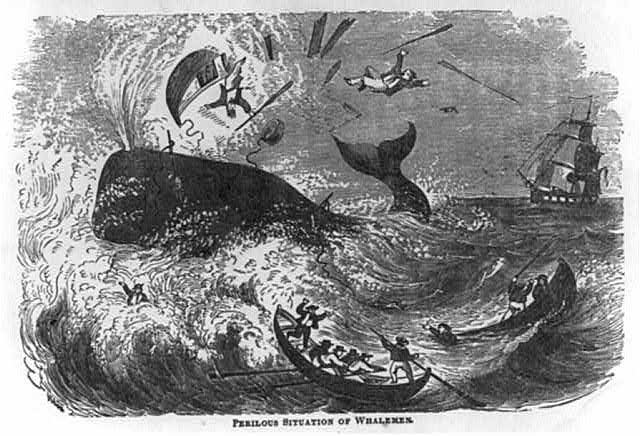

Whaling voyages could last three or four years. The work was dangerous. Sailors could be injured or drown while hunting whales.

The Arctic Wheelman, 1861

Demand for whale oil was high during the 19th century. The whaling industry started to decline when whales became scarce. Late in the 19th century, newer technologies replaced whale oil. Kerosene began to be used in lamps. Machine lubricants were made from minerals or oil found underground.

Mystic Seaport’s Charles W. Morgan Sails Again

On July 21, 1841, Charles W. Morgan wrote in his diary, “This morning at 10 o’clock my elegant new ship was launched.” The whaling ship was named after him.

During the next 80 years, the Charles W. Morgan hunted whales on 37 voyages. The whaler sailed all over the globe—including as far north as the Arctic Circle.

Cutting in a sperm whale, 1903. Library of Congress

During a voyage, a sailor went high up in the rigging. He could see for miles. When he spied a whale, he shouted “There she blows!”

Quickly, rowboats were lowered down the side of the ship. The crews climbed in and rowed after the whale. When they got close, the harpooner threw his harpoon into the whale. After the whale had been killed, it was towed to the ship. There, it was carved up. The parts that were valuable were saved.

The Morgan is the last surviving wooden whaling ship. Today, it is tied up at the dock at Mystic Seaport. It has been a museum exhibit for more than 70 years. More than 20 million people have visited the Morgan. If you visit Mystic Seaport, you can, too.

Charles W. Morgan Whaling Ship, Mystic Seaport. Carol M. Highsmith, Librar of Congress

This story is based on:

“Why the Sperm Whale Is Our State Animal” by Elizabeth Normen, Connecticut Explored, Summer 2013

“Mystic Seaport’s Charles W. Morgan Sails Again” by Matthew Stackpole, Connecticut Explored, Summer 2013

Mystic Seaport, “History of the Charles W. Morgan,” mysticseaport.org/explore/morgan/history/

“Whales and Hunting,” The New Bedford Whaling Museum, whalingmuseum.org/learn/research-topics/overview-of-north-american-whaling/whales-hunting